Reflections on a Year of Daily Memory Drawings

art .....

Later: Learning Muscular Anatomy

Earlier: Repainting

365 Drawings

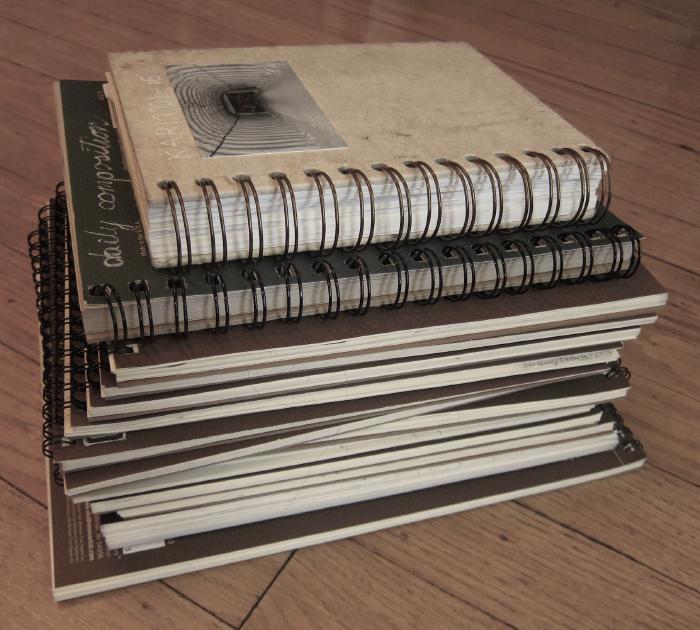

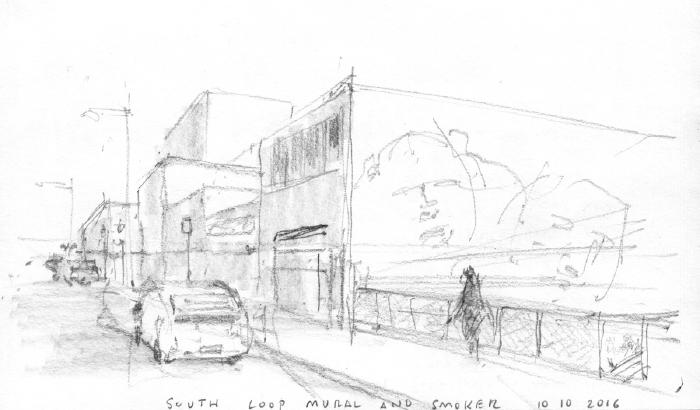

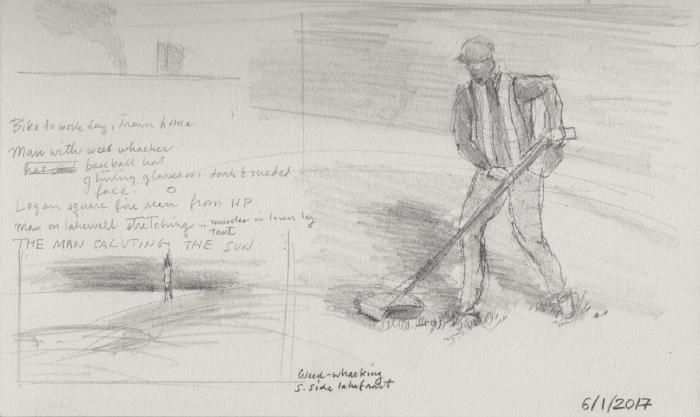

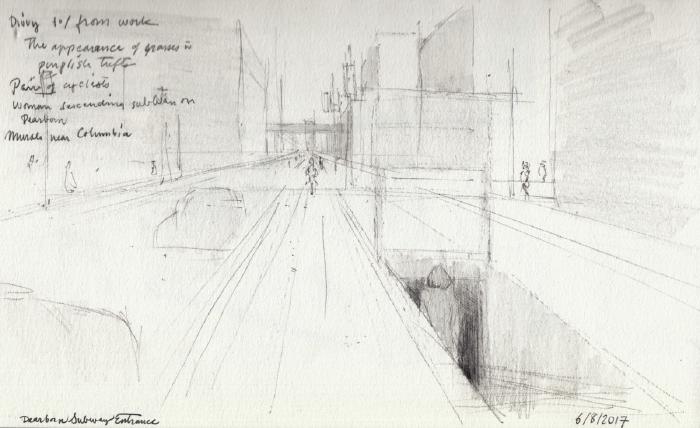

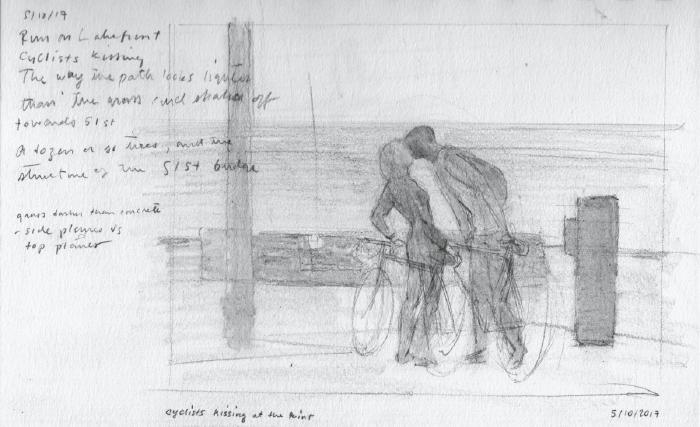

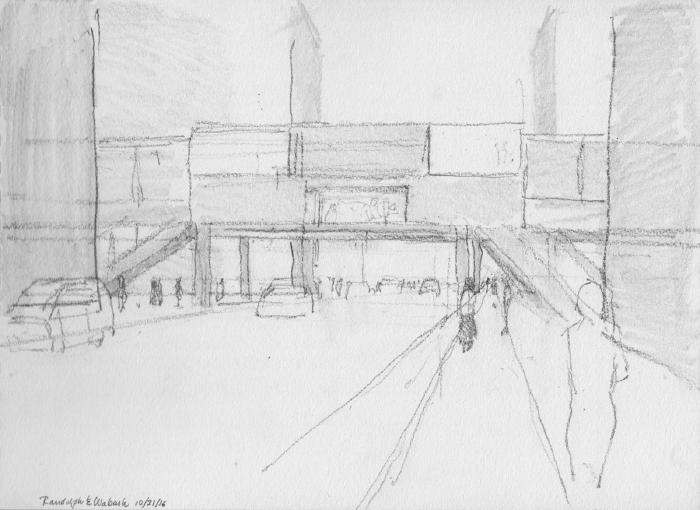

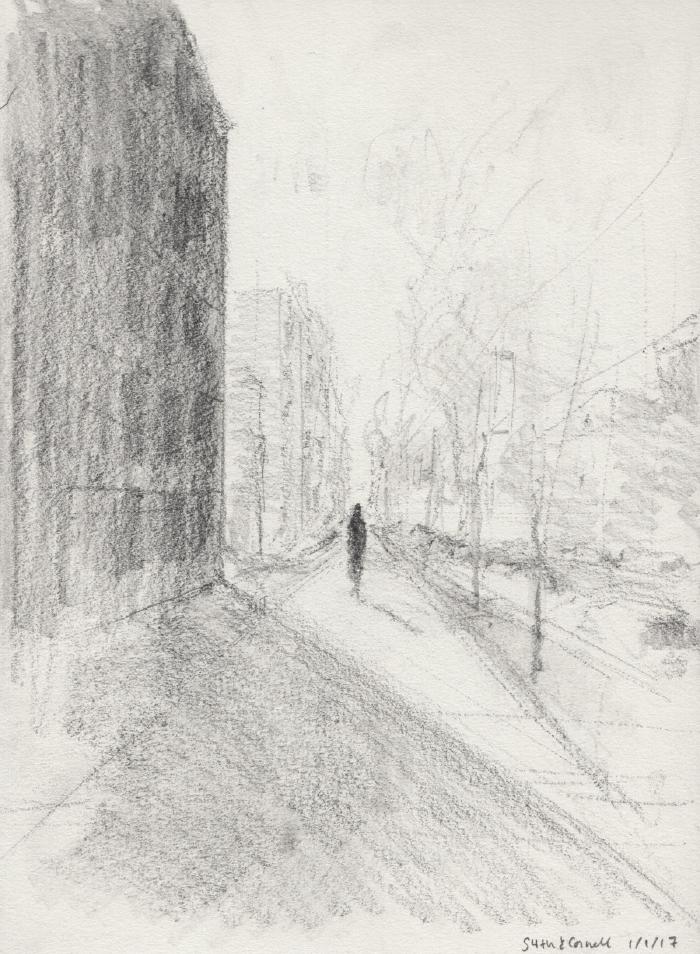

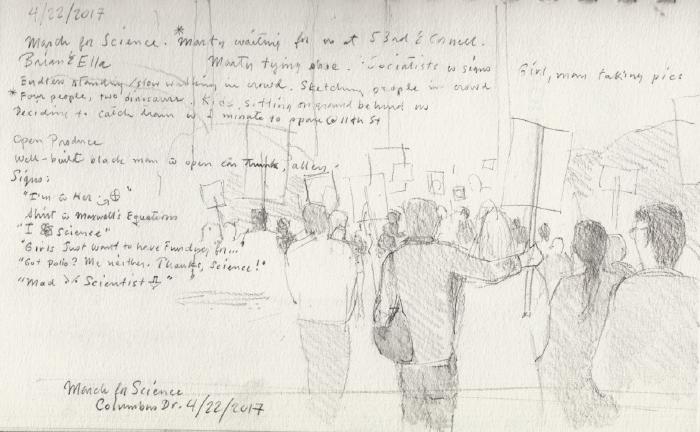

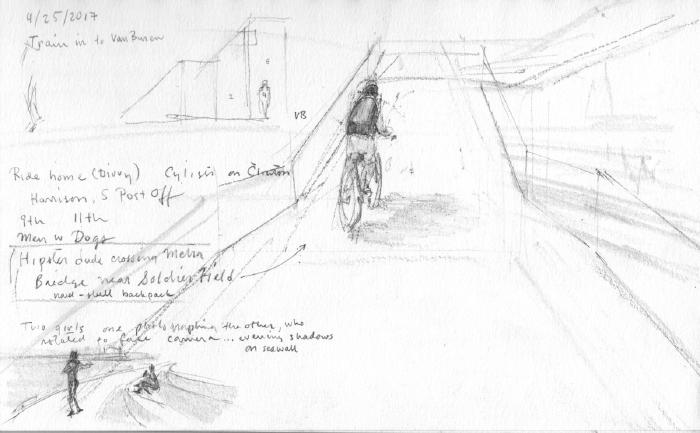

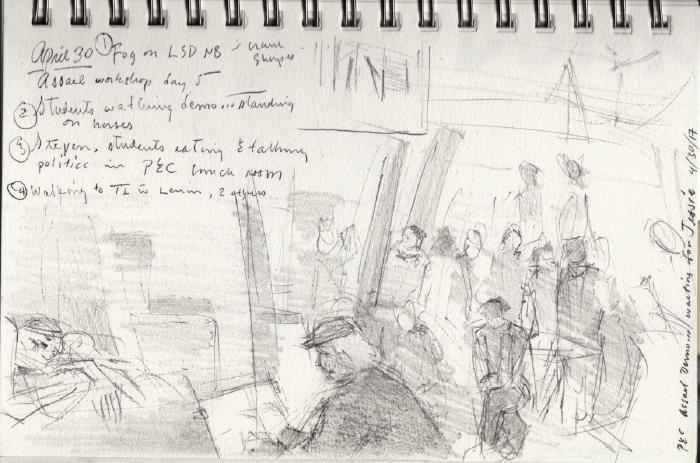

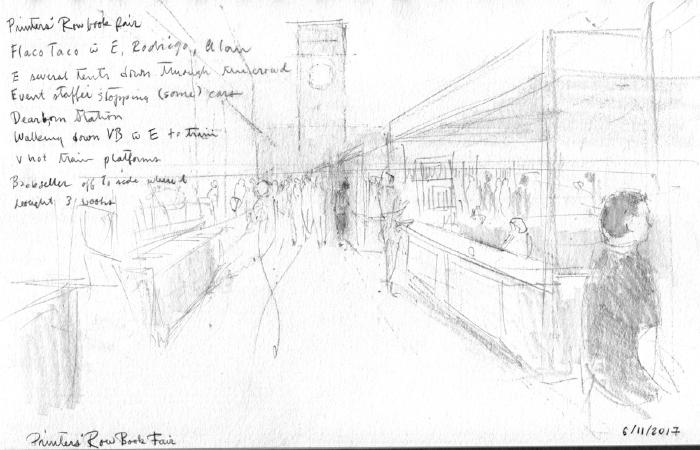

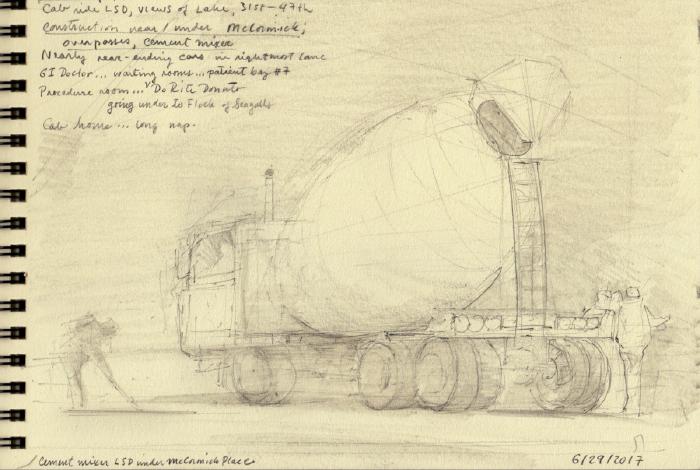

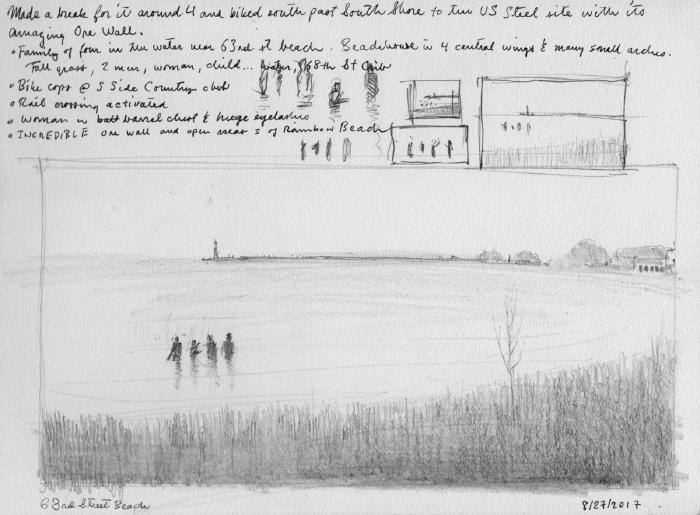

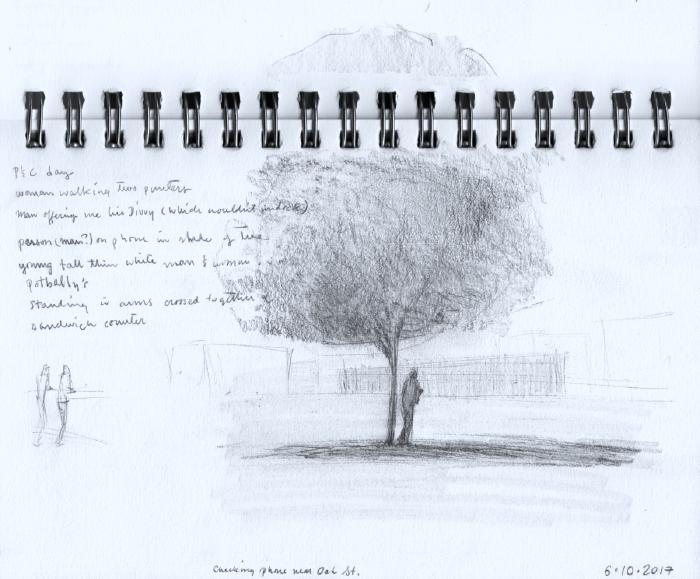

The sketchbooks shown below are the result of doing one drawing from memory every day for a year, a project I finished this month.

This drawing practice was based on the Daily Composition, which, as I explained last January, is an exercise from The Natural Way to Draw, by Kimon Nicolaïdes (published posthumously in 1941). The requirements for this exercise are as follows:

- See things and events that interest you throughout the day;

- Remember them, and

- Capture them on paper, in the form of a single image …

- … Once per day.

Each of these is challenging in its own way, and each reinforces the other. Maintaining the practice over a full year taught me a number of lessons.

Lesson 1: The limits of visual memory

I’d struggled with this exercise now and again over the years, and in taking it up again I was immediately reminded just how little I remember of what I see throughout the day.

The mind is able to recognize, and, to a greater or lesser extent, to respond mentally and emotionally to a stunning variety of objects and occurrences in the world around us. This happens automatically and without effort. But this sort of ordinary seeing is not the same as being able to recall and to visually reproduce the things we "see."

To demonstrate this to yourself, try to draw your spouse's face, or a friend's, from memory. This is a person you would have no trouble recognizing, even at some distance, yet you don't really have access to how your brain stores that information. Now try to draw your car, or bicycle, or the front of your building. These are things you know well, yet you probably cannot describe them visually in much detail.

Doing this exercise faithfully made this fact painfully obvious. Each day, out of the millions of details that passed in front of my eyes, I was left grasping only a handful of facts to work with at day's end. (The number of memories was small, but I was surprised that it was never zero.)

Contrast this with the capabilities of a camera: it faithfully records the details it is exposed to, millions of bits of data per shot. But the camera, a mere machine, cannot recognize or react emotionally to those details1.

Lesson 2: Trying to remember amplifies seeing

It would be easy to think of the Daily Composition exercise as a way of learning how to do a camera's job: you are exposed to scenes, and later you record them on paper. I did find myself, in fact, taking mental "pictures" most days, of a person or group doing something, in some specific place. I would see a person getting into a cab, or construction workers huddled over a hole, or (one day) a unicycle rider cresting a small hill, and I would think, "that's it!" and try to remember, for that evening's drawing, everything I could about the moment I'd just seen.

During the course of the year, I didn't actually get that much better in terms of the sheer number of details I could recall. A half dozen "facts" (the size and shape of a doorway; the size and number of windows in a storefront; the particular shape of a woman's boots), along with a rough gesture for and/or placement of the key figures, were about as I could expect for any given day's drawing.

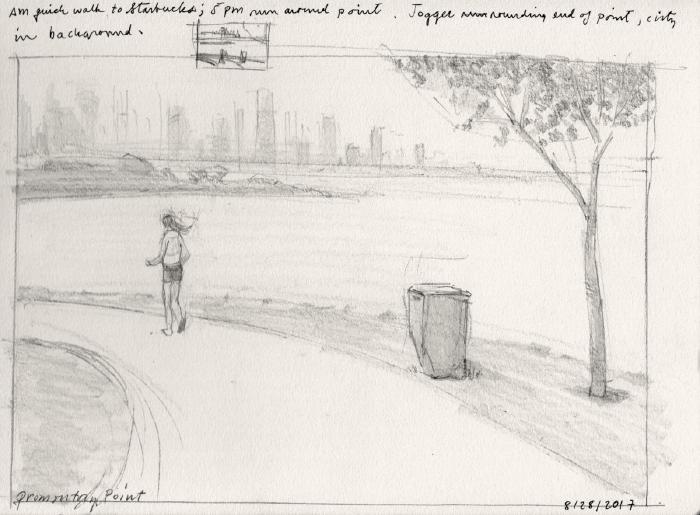

A much bigger change occurred in my ability to notice things, and my emotional response to them was amplified. Knowing that I needed material for a drawing at the end of the day simply opened my eyes more. It was like going on vacation somewhere totally new. I saw things in my neighborhood, and on my commute, that I had passed by without noticing for years: the shapes and placement of signs, light poles, fire hydrants; the construction and weathering of steel supports for elevated trains; the multitudes of ornamental details on buildings. The endless variety of people's faces… commuters, shopkeepers, construction workers, homeless men and women; the smiles, grim stares (especially at commute times) or lines of care they bore; their postures and gestures (all too often, in relationship to their phones); the cut and fit of their clothing, coats, boots or shoes. The endless repetitive movements of pigeons, and the surprising variety of other birds (sparrows, hawks, cranes, herons, geese, ducks, swallows, and several migratory bird species I couldn't identify). The printed word, in steel or brass relief, to be seen everywhere in streets and sidewalks, indicating lines of survey, or the origin or builders of utility covers or nearby buildings. All the endless varieties of trees, contours of trunks, branching patterns, leaves, and all the grasses, flowers and weeds of the city… these things came to my notice, were revealed fresh as though I had previously had some sort of screen over my vision that had fallen away.

Part of seeing these things became caring about them. In that regard I became less, not more, like a camera.

Lesson 3: Emotion aids recall

If I saw something I reacted to emotionally, it was usually a lot easier to recall later. This seems obvious, but to live the connection between emotion and memory as part of one's daily routine for a year had a cumulative effect. This is what I meant when I said in my last post that I felt a stronger connection to Chicago and my surroundings. I suspect that building these sorts of connections to daily life is one of the main reason Nicolaïdes recommends the exercise as a daily practice.

Lesson 4: Other tricks for remembering

Aside from focusing on things that give an emotional charge, here are some more tricks I used to remember things I saw:

- Practice drawing or painting something while you look at it. This includes making movements in the air as if you were drawing, building a little actual muscle memory (and inviting curious glances from passersby).

- Re-remember things. If I saw something I wanted to "save up" for the evening's drawing, then whenever I saw something else that looked interesting, I would look carefully at it, but then I would use the whole noticing-something-noteworthy experience as a reminder to remember the other thing I was trying to remember also. In other words, every new thing I noticed became a reminder to remember the other thing. Occasionally, I would build a list of things to remember and would then go through the list items one-by-one whenever this occurred.

- De-distract and focus. Of course, sometimes the above tricks got to be too much; at those times, I'd try to minimize my visual input by looking down at the sidewalk if safe to do so (allowing my peripheral vision or looking up when needed, in order to keep from getting hit by buses, etc.), just making the effort to hold the memories in my mind while I walked or ran.

Lesson 5: Invention and knowledge help fill in details

Given a relative paucity of remembered facts, how do you complete your drawing? Just as our mind fills in details about what we see without our being consciously aware of it, one can invent the elements of a scene that elude our grasp when we try to recall them. For this, a knowledge of perspective, of human anatomy and clothing, of the construction of builings and plants and trees, and especially of light and shadow are indispensible for adding extra life and believability to a composition, no matter how quickly executed. For example, I would rarely remember a specific shadow, but if I knew where I was and what time it was, I could place the shadows based on where the sun would have been at the time. Used skillfully, invention can also amplify whatever emotional response led one to record the scene in one's mind to begin with.

I think I got slightly better at "filling in the gaps" this way over the year. The exercise does seem to strengthen the connection between memory, knowledge, and imagination.

Lesson 6: Drawing can distort memory; revisiting a place helps

I often noticed that, after drawing something that occurred in a specific place, my memory would be strongly affected by whatever inventions (or mistakes) I came up with to compensate for my ignorance of the drawing's setting. For this reason, I sometimes disliked looking at the drawings after the fact because they were so clearly wrong and they interfered with my "real" memory of where the event occurred. An easy remedy for this was just to go back to the place in question and look around. One sees many more details the second time around, and it's always amusing and humbling to realize how wrong you got it the first time.

On a related note, I find that taking and reviewing photographs shapes my memory as well. I remember things differently, and more emotionally, having drawn them, either from life or from memory, than I do when I've photographed them. I sometimes limit my photography when I travel for this reason (although I still take a ton of pictures).

Lesson 7: Don't make it a big deal

To do the exercise three hundred and sixty five days in a row did require commitment, since I have a busy schedule and was generally doing it at the end of the day when my willpower budget and my ability to focus were all but spent.

Nicolaïdes makes a point of not making a big deal of these drawings, setting a fifteen minute time limit for each. I broke this rule many times, especially at the beginning when I would try to recall as much as possible. Eventually, however, I settled for just jotting down a few things I remembered seeing (sometimes starting with just remembering where I was and what I did, which could be hard enough), and turning the most compelling memory into a small composition. Even on days when I was the most busy and distracted I could typically remember at least one thing to put down on paper. And I found there was only a loose correlation between how much effort I put into remembering things throughout any given day, and how much I liked the drawing at the end of that day. Some days I was excited about the results, and some days I was just happy to put the drawing away afterward. Part of what's good about doing something like this is you can fail over and over again, and your daily commitment to the practice means that any specific failure is no big deal.2

Lesson 8: More can be better

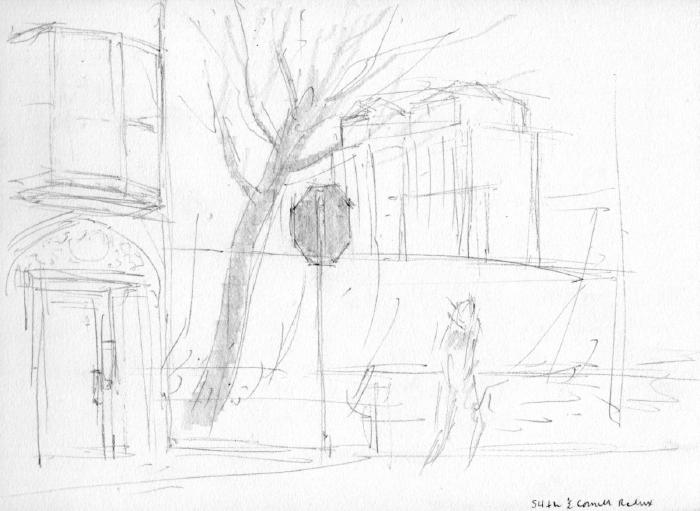

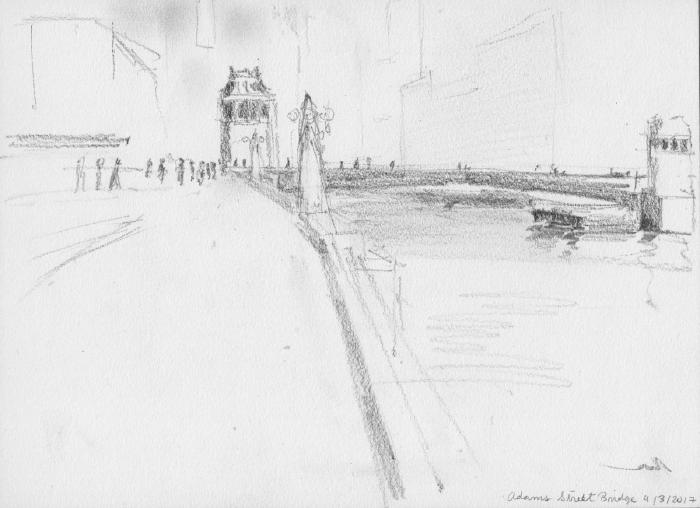

At least half the drawings are so bad, I find them pretty painful to look at now. Many of them show an interesting tidbit or idea worth developing further. And a small fraction, less than 10%, I enjoy looking at and find appealing on their own terms. Some of these are shown here.

The few successes illustrate an important rule that I still struggle with: with art making, sometimes quantity wins. I prefer to work for a long time on paintings, but it is nice to complete something every day and, occasionally, to have it succeed. No matter who you are, I suspect if you make a drawing a day for a whole year, at least a few of them will suprise and please you.

Lesson 9: It's about composition

Composition is about choosing what goes in a picture and arranging those things in a pleasing design which communicates one's ideas or intentions. One reason I took up this practice is that I find inventing compositions (e.g., in the studio) more challenging than finding them directly in front of me. Ultimately, memory and rendering are only part of the practice… the rest (perhaps the biggest part) is design. Nearly four hundred drawings later I still find it challenging, but solving a specific design problem every night has made the whole problem of composition seem tractable in a way it didn't before. This, I imagine, was another reason Nicolaïdes emphasized this exercise.

Moving forward

It will be helpful if you keep this up for a year, and it will be twice as helpful if you keep it up for two years. The really serious student will make a quick composition every day for the rest of his life despite everything else he has to do. –Nicolaïdes

In later chapters of The Natural Way to Draw, variations on the Daily Composition are introduced, including a greater amount of invention, and revisiting the same scene over several days in an extended composition. For myself, I wanted the challenge of working primarily from memory for a year, but have increasingly been craving more time for both invention and for working from life. I intend to continue regular compositional practice, but more as a natural and playful part of my creative rhythm, rather than as a tightly-defined daily practice. I don't know where it will lead, but look forward to finding out.

More Drawings

Here are a few more drawings from the year.

Later: Learning Muscular Anatomy

Earlier: Repainting