Man on Wire

misc .....

Later: Photoshop on a Dime

Earlier: South Pole Videos

Growing up in the Midwest speaking English like everyone else around me, I always thought my native tongue was somewhat ordinary, even ugly. In high school and beyond, I loved studying French for the glimpses it afforded into other ways of thinking, ways which I may have presumed were more culturally sophisticated. French was the language of Baudelaire, of wine and cuisine, of Louis XIV and Napoléon; of Monet, Delacroix, Ingres.

I think it took me many years of reading English prose and making small forays into other languages (something I still enjoy) to truly appreciate how marvelous a language English really is. For one thing, at roughly 1 million words, it far outstrips most other languages in terms of vocabulary (though perhaps half of those are technical terms). The sheer lexicographic heft of English provides enormous expressive power — when several similar words exist for the same thing, one can choose the one with exactly the right associations or poetic impact.

Yet, as with any language, English has words whose equivalents in other languages are more beautiful. “Beautiful,” for example, is not a beautiful word. It sounds a bit prim, or prissy. “Beau,” on the other hand, is such a simple word, barely an exhale, or a sigh. It is far superior to its English cousin, in my opinion.

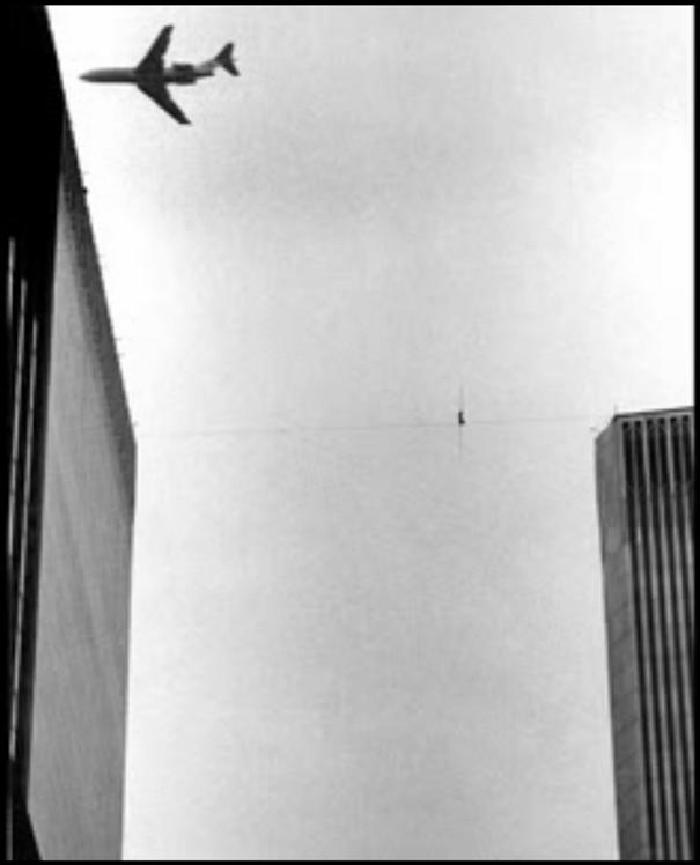

“Beau” is a word you hear a lot towards the end of Man on Wire, a film by James March which portrays the efforts of Frenchman Philippe Petit, in 1974, to cross between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center on a tightrope. While the film itself is very well made, what is particularly captivating is the story — how Petit and his friends combined vision and inspiration, careful planning, stealth, stamina and, above all, courage, to stage an act which transformed not just themselves, but also the public’s view of the Towers.

I was somewhat incredulous to hear, years after the fact (I was only eight years old at the time of the stunt) that someone had tightroped between the two buildings. Now, of course, the imagery in the film is amped and torqued in gut-wrenching ways by the ghastly absence of the Towers themselves and the collective memory of their destruction, burned on the retinas and the psyches on so many of us who remember seeing them fall on live television. Yet the tears shed by the participants in the film, interviewed decades after the fact, do not seem to be about the fallen towers themselves, but about the purity and intensity of the moments before, during, and after Petit’s walk, and the beauty created, however briefly, on that day — August 7, 1974.

Seeing the film (made just last year) transforms the memory of the Towers from one of trauma to something more like transcendence. One of the film’s ironies is that it invites comparison between the clandestine, overseas preparations of the youthful Petit and his friends to what one imagines the nineteen hijackers’ final months and days were like (it would make an interesting film to try to capture their point of view honestly, but I doubt the world is ready for such a film). The contrast, very vivid, and never stated in any form in the film itself, is an obvious one: the sheer horror of Sept. 11, versus the joy and amazement generated by the simple feat of walking between the two buildings, more than 400 meters above the streets below. Yet perhaps it shows the power of art that such comparisons fade when one is shown Petit’s feat on its own terms. In the space left behind by the towers, one imagines the space between them — and the courage required to face imprisonment by a foreign police force or, equally likely, death at the hands of high winds and gravity. To achieve the impossible — not for the sake of destruction, but for beauty. Comme c’est beau.

Later: Photoshop on a Dime

Earlier: South Pole Videos