Resources for Learning Clojure

Later: Processes vs. Threads for Integration Testing

Earlier: Continuous Testing in Python, Clojure and Blub

I thought I’d take a moment to present one possible path, or set of alternate paths, for learning Clojure, a modern Lisp implemented on top of the Java Virtual Machine.

Update: Since this was written in 2012, a number of additional excellent books have come out. These include Carin Meier’s Living Clojure; Vandgrift and Miller, Clojure Applied; and Daniel Higginbotham’s, Clojure for the Brave and True. These are all great choices, and Clojure for the Brave and True is a strong competitor for the best introductory Clojure book.

In addition to a surprising number of very good resources out there for such a young language, there are resources specific to other Lisps which map reasonably well onto Clojure.

Clojure does have a learning curve, especially for one coming from imperative languages such as Java, Python, C++, or Ruby. These languages are, in some ways, more similar to each other than they are to functional languages such as Clojure (though they all have features which were pioneered originally in implementations of Lisp, one of the oldest computer languages).

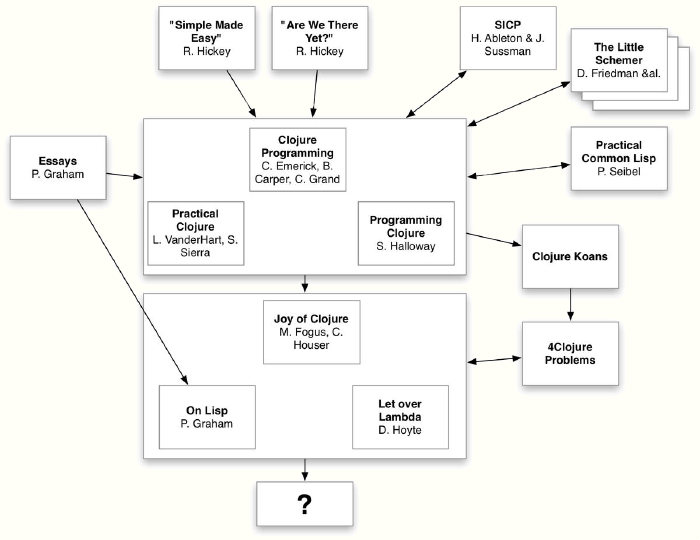

Since the approach I took was somewhat haphazard and I have the benefit of some hindsight now, I present here a rough sequence which might make the road a little less bumpy for others. Though not an exhaustive list of resources by any means, the following diagram summarizes the discussion points that follows.

The approach I recommend goes something like this:

If you are going to pick just one of these resources to get started, I recommend the O’Reilly book Clojure Programming by C. Emerick et. al. I have both the PDF and print versions of this book, and it’s not only an excellent book on Clojure, it’s one of the best O’Reilly books I’ve seen in the dozen or so years I’ve been reading them. The other two books are also good (I have not checked out the 2nd edition of Programming Clojure yet)… Clojure is particularly blessed in having not just one but at least three excellent “starter books” on the language.

If you’re curious why one might want to learn a Lisp as your next (or last?) programming language, Paul Graham evangelizes very effectively about Lisp in some of his many essays. You might want to check those out before diving into Clojure per se.

Additionally, videos of Rich Hickey’s talks, particularly Simple Made Easy, though not so much about Lisp or Clojure per se, explain the challenges and limitations involved with stateful Object-Oriented programming and motivate the ideas behind functional programming in general and Clojure in particular. I very much recommend these videos, though reaction to them among programmers I’ve shown them to has varied wildly from enthusiasm to extreme irritation.

People with exposure to Common Lisp or Scheme may be familiar with Abelson and Sussman’s Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs; Friedman’s The Little Schemer and its sequels The Seasoned Schemer and The Reasoned Schemer ; and P. Seibel’s Practical Common Lisp, which I’ve only peeked at but which has an excellent reputation. These books could provide a gateway into Clojure, or might merit a look at once you’ve got some Clojure basics under your belt. I find them to be interesting supplemental reading.

Before getting to the more advanced books, the Clojure Koans are a fun and pleasantly gradual way to start reinforcing your Clojure basics (I worked most of them on various airplane flights to the South Pole last year). Similar but somewhat more challenging are the 4clojure problems (I’m about 3/4 of the way through these).

I find these kinds of problems alternately soothing (when I get them right away) and maddening (when I actually have to work at them). They are like crossword puzzles for programmers, and they do really help reinforce the material from the books. Due to the way the problems are implemented, they are unfortunately limited in terms of how they cover Java interoperability, macros, and concurrency.

After you’ve read an introductory text, worked some problems and maybe started one or two personal projects with the language, you’re ready for The Joy of Clojure. This book is somewhat hard to describe; I started it too early, then came back after six months and it made a whole lot more sense. The best way to explain The Joy of Clojure is that it helps you to understand both some of the quirks of the language and what makes it truly great, and will help you evolve from writing clumsy translations of what you’ve learned in other languages, to truly compact, elegant, idiomatic Clojure code.

After, or perhaps during, Joy of Clojure, take a deep dive into macros, the secret sauce of Lisp. Macros allow one to implement new language features in order to make one’s code elegant and expressive, and to optimize the fit to one’s problem domain. Paul Graham’s On Lisp is mostly about macros; Hoyte’s Let over Lambda refers to On Lisp many times and builds on some of the foundations laid in that book.

To summarize (strongest suggestions in bold):

- Graham essays

- Hickey videos

- Introductory book (Clojure Programming, Programming Clojure, or Practical Clojure)

- Possibly detour into SICP, Practical Common Lisp and/or The * Schemer books

- Clojure Koans

- 4Clojure Problems

- Joy of Clojure

- On Lisp

- Let Over Lambda

There are many other Lisp books which I haven’t read yet, as well as a Clojure book or two I’ve left out. Also, lest I forget, the Clojure community has a reputation for being extremely welcoming and helpful. There is a Google Group / mailing list and an IRC chat as well.

The bottom line is that for such a young language (or young variant of an old language), we are fortunate to have such a rich selection of resources to pick and choose from. Enjoy!

Later: Processes vs. Threads for Integration Testing

Earlier: Continuous Testing in Python, Clojure and Blub